"At Sword's Point" will be broadcast on 88.5 NEPM on Sunday, Sept. 1 at noon.

American labor unions have seen an incredible resurgence in recent years, which begs the question: why were they in decline in the first place? "At Sword’s Point" revisits a pivotal moment in American history, when the furious power of Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare found its first true target, and when the dismantling of American organized labor began. But this isn’t a story of workers caving in the face of mass hysteria; this is the story of a rural town where, against all expectations, the workers fought back.

This hour-long radio documentary, hosted by public historian Tom Goldscheider, recounts these dramatic events of the early 1950s, while also providing important context on the machine tool industry of Greenfield, Massachusetts — once a center of global innovation — as well as the origins of the United Electrical Workers Union, or UE.

Tom Goldscheider is a public historian and working farrier based in western Massachusetts. His research on Greenfield labor history was published in the Historical Journal of Massachusetts (Winter 2019) and shared through a series of talks given at area venues. He has also published and spoken on the origins and significance of Shays’ Rebellion, and developed an interactive curriculum on local abolitionist history for the David Ruggles Center for History and Education. He holds a Masters in History from the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Ian Coss is a creator of acclaimed podcasts. His nine-part

documentary The Big Dig was named one of the best podcasts of 2023 by The New Yorker and Vulture, while spending over six weeks in the top 100 shows on Apple Podcasts. Previously, his audio memoir Forever is a Long Time was named one of the best podcasts of 2021 by The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and Apple Podcasts. His work has appeared on Snap Judgement and 99 Percent Invisible; it has been featured at the Tribeca Film Festival, and recognized with multiple Edward R. Murrow Awards as well as a nomination for podcast of the year from the Podcast Academy.

"At Sword’s Point" is produced with support from New England Public Media, Mass Humanities, the Museum of Our Industrial Heritage and the Greenfield and Montague Cultural Councils.

At Sword’s Point

ARCHIVAL (HUAC Hearing): the question is, have you ever been a member of the Communist party?

NARRATION: Today, the Red Scare is best known for Congressional hearings that featured Hollywood stars and liberals working in the State Department,

ARCHIVAL: HUAC hearings

NARRATION: But it really got its start with labor unions.

Matles Speech: During the McCarthy period, This union bled. How can any one of us who has gone through those days, those months and years, ever forget it?

NARRATION: My name is Tom Goldscheider. And this is "At Sword's Point," a radio documentary about American labor at the crossroads.

Over the next hour, we’ll explore how the dismantling of organized labor began. And also, the story of a town where, against all expectations, working people fought back.

NARRATION: One chilly April morning in 1952, a large crowd gathered under the marquee for the Garden Theater in Greenfield, Massachusetts. The film advertised overhead was “At Sword’s Point,” a swashbuckling tale about French musketeers.

ARCHIVAL (At Sword’s Point film): The year 16 forty-eight was a grim one for France. Terror and violence ruled…

NARRATION: But the crowd wasn’t there to see the movie. They were there to cast a vote.

Everyone in the crowd that morning had two things in common: they worked for Greenfield Tap and Die, the area’s largest employer, and they belonged to the United Electrical Workers union. The union had handed out leaflets at the factory gates the day before, telling workers to appear at a Mass Meeting first thing in the morning. Over a thousand men and women turned out. They listened to speeches and were then called to the front of the theater in alphabetic order to cast secret ballots.

NARRATION: Now under normal circumstances, this vote would have been an important local news story that affected maybe hundreds of families. But the circumstances surrounding this out-of-the-way place in the early 1950s were anything but normal. Greenfield workers found themselves in the national spotlight, embroiled in a bitter dispute that divided their union, their town and the entire nation…

ARCHIVAL (HUAC Hearing): the question is, have you ever been a member of the Communist party?

NARRATION: My name is Tom Goldscheider, I’m a public historian based in western Massachusetts. And this is "At Sword’s Point," a radio documentary about American labor at the crossroads.

Greenfield workers surprised everyone that April morning – and not for the last time. For a brief moment, these workers took center stage in a national drama called the Red Scare. Before we get to that, we need to get to know who these workers were, and why they joined the union they did. But we start by getting to know what it was they made.

Jim Terapane: So one of the things we offer our visitors is a, you know, an actual chance to use these tools we talk about…

NARRATION: Jim Terapane is a journeyman machinist and historian at the Museum of Our Industrial Heritage in Greenfield. He gave my co-producer Ian Coss and me a demonstration of the revolutionary technology at the heart of our story.

Jim Terapane: Yeah, well, that's what we have here.

NARRATION: Those tools he's talking about are called taps and dies.

Ian Coss: So this is, is this the tap or the die?

Jim Terapane: This is a die and it's a hardened piece of tool steel that has the form of the thread cut into it.

NARRATION: We’re all familiar with nuts and bolts. They're everywhere. There are literally thousands of them in a single car. But in order to work, the threads inside every single one of those nuts, have to mate perfectly with the threads on every one of those bolts. For most of human history, that kind of precision was impossible.

Um, it's that important a place in the, in, in, in the machine world. It's almost mythical, really, because they're the devices that make our world work.

Jim Terapane: the ability to make even a simple nut and bolt You know, in 1870, that was like science fiction.

NARRATION: But in 1872, a machinist working in the Connecticut River Valley patented a set of hand tools called taps and dies. The die looks almost like a socket wrench. But at its center is a series of angled grooves made from hardened steel that are hard enough to cut threads right into a metal rod.

Jim Terapane: So we use a little cutting fluid, because that always helps. We're cutting brass, which isn't that hard.

I'm almost standing over it.

NARRATION: Jim presses the center of the die onto a metal rod and starts turning it...

Jim Terapane: Now it takes a little bit to get it to bite and start going in,

NARRATION: As the die works its way down, that brass rod is transformed into a brass bolt.

Jim Terapane: Here's the counterpart.

NARRATION: The tap is a perfect inverse of the die. It looks more like a drill bit. What it does is cut a perfectly spiraled groove, or thread, into the inside wall of a pre-drilled hole. Moments later, Jim hands us a matched set: one bolt, one nut.

Ian Coss: Snug fit,

Jim Terapane: yeah, perfect, try it, try it, and you can, you can have it as your souvenir for today.

NARRATION: It's hard to overstate just how radical this technology was in 1872.

Jim Terapane: threaded devices and cutting tools were like the holy grail. It's the one thing that everybody's been trying to do for literally centuries is to find a way to fasten things together permanently, or be able to unfasten things that you can prototype.

NARRATION: No one had figured out how to mass produce consistent and reliable screw threads, until now.

Jim Terapane: And when you think of the sweep of history in technology, it took from the middle ages until the mid 1800s to figure out how to make a nut and bolt and within 25 years, we're flying airplanes and there's a direct connection to making that happen.

NARRATION: The demands of this new technology created the need for a new trade: the precision steel tool machinist. For centuries, blacksmiths had forged heated iron to make tools and hardware, now machinists harnessed water power to cut pieces of steel into finely calibrated tools and parts, measured in thousandths of inches.

And one of the centers of this new trade was the isolated town of Greenfield. The town was famous for making steel knives and chisels, so skilled machine operators already lived there. Soon, local investors opened several competing plants in town that made threading tools. By the end of the 1800s, Greenfield produced more taps and dies than the rest of the world combined – making the tools that made mass production of things like locomotives and cars possible.

Jim Terapane: And if you're a machinist anywhere in the world, you know about Greenfield. It's that important a place in the machine world. It's almost mythical really because there the devices that make a world work.

NARRATION: There was no talk of unions or strikes in those early years. For one thing, these were among the highest paid workers in the industrial world. There is no row housing in Greenfield today; the machinists who worked here owned their own homes and made good lives for their families. They saw union organizers as “outsiders” and put their trust in their employers who, like them, were born and raised here in Franklin County.

But then there was a paradigm shift.

A group of Boston investors wanted a piece of this highly lucrative industry. And in 1912, they engineered a forced merger of the largest tool companies in town to form the Greenfield Tap and Die Corporation, or GTD for short, the first publicly-traded business in Franklin County. And the merger coincided with an exponential growth in profits.

ARCHIVAL: America is called to arms. In New York, the first volunteers are cheered down Fifth Avenue…

NARRATION: World War I was the first fully mechanized war. Both sides relied on taps and dies to make their armies work, and both sides bought them from GTD, accounting for half the company’s sales.

ARCHIVAL: Truly, the use of screw threads is the key to modern manufacturing methods, where disassembly, interchangeability, and freedom from distortion are paramount.

NARRATION: Production grew so rapidly during the war, that a group of overworked machinists at GTD walked off the job demanding an eight-hour-day with overtime pay. This was not considered an organized strike since they did not have the backing of a union. And it didn’t succeed: Management hired replacement workers, and fired the men who led the walkout. That trust the workers had put in their company was being tested. Again, Jim Terrapane.

Jim Terapane: You know, that's what happens when, uh, you lose local control. And that's a big part of the story here is that for hundreds of years being isolated out here in a rural area for so long, people became independent and they know that works and they know what doesn't work.

NARRATION: And things only got worse. By the 1930s, Greenfield Tap and Die was run by a Board of Directors who had no connection to Franklin County and no knowledge of how precision tools were made. It didn’t help morale when the Board brought in a new president, Donald Millar, a Wall Street banker who went home to Manhattan on weekends to be with his family.

This was not how tool and die companies traditionally operated.

Jim Terapane: These early factories you weren't allowed to be the manager of the factory unless you served an apprenticeship, worked on the floor, became a foreman, very much like the military.

NARRATION: The new managers said they wanted to, quote, “rationalize” production at GTD, or maximize the productivity of each individual worker. They hired outside contractors onto the shop floor to conduct what were called “time studies.”Men in lab coats stood behind machinists with stop watches and timed each individual task that went into the work they performed. The data they collected was used to set pay rates throughout the plant.

Jim Terapane: We're talking about people operating sophisticated, dangerous machinery, you know, skills that take years and years and years to develop. And then you have someone with no knowledge of those constraints, basically telling you, you need to push the machine harder or, you know, maybe cut corners, uh, and so those two things just don't, don't mesh.

NARRATION: GTD workers finally hit a tipping point in 1940, and decided to launch a union drive.

ACTOR READ: Everybody was so fed up by that time that even the “Old Guard” thought the union was a good idea.

NARRATION: These are the words of James Wooster, a machinist who worked there at the time, taken from an oral history account.

ACTOR READ: Of course, that was only Plant #1. It took us another year to get Plant #2 because they’re way up on Sanderson Street right next to management. We could always be more militant because we were always further away from the bosses, and they never knew what was going on with us.

NARRATION: Now there were a lot of different jobs to do at GTD, but it was the machinists who led the drive to unionize. Everyone assumed they would sign on with one of the older, so-called craft unions, that only represented machinists. Instead, they invited in a union that was barely four years old and was creating a lot of buzz at the time. This was the United Electrical Workers union, or the UE, the same union that would turn Greenfield into ground-zero for a national struggle in the early days of the Red Scare. That’s coming up.

NARRATION: My name is Tom Goldscheider and this is “At Sword’s Point,” a radio documentary about a pivotal moment in American labor history. When we left off, workers at Greenfield Tap and Die had just invited in a new union: the United Electrical Workers, or UE.

AMBI: Nurses strike

I first learned about the UE while walking the picket line in support of striking nurses at the Greenfield hospital, where my wife works.

AMBI: (Audio of Greenfield nurse’s strike): We also, very importantly, need to have charge nurses for each unit. Yeah. Twenty-four hours a day. Yeah.

NARRATION: I fell in talking with an older machinist who told me stories he had heard as a young man, about a time when the whole town was to apart by a labor dispute that got national attention. As we turned the corner onto Sanderson Street, he pointed out the old headquarters for the company at the center of it all. In a building now owned by the hospital, the words “Greenfield Tap and Die” are etched in stone over a handsome archway.

ARCHIVAL: Nurse strike audio fades

NARRATION: Before we parted ways, the machinist introduced me to a pair of retired union organizers in town who are a married couple: Judy Atkins and Dave Cohen. They offered to take me up to the local office for the union I’d just heard so much about. A few weeks later, the husband let me into the office for UE Local 274 on a quiet side street above an ice cream shop. It was there I learned that the UE was one of the first of what were called “Industrial Unions.” Here’s Judy Atkins.

Judy Atkins: Industrial unionism means every worker in the workplace belongs to the union. There's not a division between skilled worker and unskilled worker. And there's no division between men and women or different races…everybody's in the union.

Tom Goldscheider: And what are the advantages of that, do you think?

Judy Atkins: Strength and power, right? It'd be very hard to divide and conquer when everybody's together.

NARRATION: Today, we know of the AFL-CIO as America’s biggest labor organization, but once these were two very different, almost opposing, organizations. The Congress of Industrial Organizations, or CIO, split from the established American Federation of Labor, or AFL, over this very issue of who could and who could not join the union. The AFL was much more restrictive.

Dave Cohen: they would organize in a factory just the skilled workers, say, the tool and die makers.

NARRATION: That’s Judy’s husband and fellow UE organizer, Dave Cohen.

Dave Cohen: And there might be, in a big factory, 30 tool and die makers and 800 other workers. And so if those 30 went on strike, the rest of the workers would go to work, and it was easy to replace 30 tool and die makers. So in the 30s, it really became the idea of Industrial unionism. Everyone had to be in the union.

NARRATION: The UE was part of that new wave of industrial unions, and Greenfield machinists were signing on. In 1941, just months before Pearl Harbor, the workers at Greenfield Tap and Die voted in the UE by a margin of almost 2-1.

Those machinists had learned the value of including everyone in the union during World War I, when they walked out, and the rest of the plant kept running without them. Their new union – UE Local 274 – would represent almost everyone who worked at GTD: men and women, from machinists and metallurgists, to shipping, maintenance and assembly workers. And unlike traditional AFL trade unions that were run by central bosses, Local 274 ran itself. They drafted their own bylaws, elected their own officers, and voted to ratify contracts and go on strike.

Tom Goldscheider: There's a lot of voting going on.

Dave Cohen: A lot of voting going on, yeah. That's right.

Judy Atkins: And I just want to say that the experience with the UE was, I'd say, my first and only experience of democracy, of real democracy.it meant involvement, going to meetings, taking a role, you know, being responsible, and also when a vote was taken and the majority spoke, that's what you went by. And so it was, it was real eye opening to me, as a person, to experience What democracy really was, really is

NARRATION: Every workshop within the plant also elected its own shop steward, who helped settle disputes with the shop foreman, who represented management. This was a complete game-changer for workers who often had to work under incompetent or unscrupulous foremen. Thornier disputes were passed on to a Grievance Committee staffed by members of the Local.

Dave Cohen: If you're in a non-union shop and you go complain to the boss, you can get fired. You know, democracy doesn't exist inside a workplace in this country. Uh, if you don't have a union, you're an employee at will and the boss can do with you what they want. When you have a union and have a grievance procedure, you have every right to complain to the boss and you can't get fired.

NARRATION: The new union was very popular with workers at Greenfield Tap and Die. It gave them a voice they didn’t have before and improved their pay, benefits and time off. They weren’t alone in this. The UE tore through the machine tool industry like wildfire in the early 1940s. Here is James Matles, a Romanian immigrant who rose into top leadership at the UE, speaking at a labor convention:

Jim Matles: I'll tell you what happened to me. In my first shop meeting in my own shop when we started to organize. I was elected as a recording secretary and I was eminently qualified for that job, but I had just two minor problems. I didn't know how to read or write English. I asked my president, Joe Wild, what do you do that for? He says, you're young, you'll learn.

NARRATION: When it started in 1937, the UE was made up of a handful of machinists on a shoestring budget. Less than ten years later, the union represented over 600,000 members working in 1,200 plants across the country. The union focussed on organizing workers in the booming electrical sector - think GE, Westinghouse and RCA. Here’s Robert Forrant, who is both a trained machinist, and a labor historian at UMass Lowell.

Bob Forrant: To frame it, in the early 20th century, with widespread access to electricity, we get the growth of what people Back then, used to call the white goods industries, if you think of a refrigerator or a stove or whatever. And the existing large labor organization in the United States, the American Federation of Labor, was uninterested in organizing in those industries.

NARRATION: That created an opening for new unions. The UE successfully organized GE, Westinghouse and RCA, where it negotiated national contracts so those corporations could not dodge concessions made in one plant by moving production to another plant out of state. The United Electrical Workers was the first union to affiliate with the newly-formed CIO and eventually, became its third largest member, following steel and auto workers.

Bob Forrant: It's pretty incredible if you think about it. In 1930, Most of these places, again, electrical workers, steel, auto, not unionized at all. And by 1940, they almost all are.

NARRATION: When the UE was voted in, Greenfield Tap and Die employed over 4,000 people working in three shifts, seven days a week. The company was already preparing for a war everyone knew was coming.

ARCHIVAL: There were 169 planes in mass attacks on British harbors, shipping and aerodromes…

NARRATION: Here’s Jim Terapane from the Museum of our Industrial Heritage:

Jim Terapane: During the Battle of Britain, Germany, one of the first places they attacked was Sheffield and Coventry where all their cutting tool manufacturing was. So, our industries,our thread cutting tap and die industries became indispensable in re-supplying the allies with these devices.

NARRATION: GTD was the linchpin in Roosevelt’s “Arsenal of Democracy”. Anti-aircraft batteries were set up in the hills surrounding Greenfield in case German warplanes made it across the pond. And as men working in the plants enlisted to fight, women took up their jobs.

Across the nation, unions agreed not to strike or ask for wage increases during the war years, years that were hugely profitable at companies like GE, Westinghouse and Greenfield Tap and Die for that matter. But victory in the war overseas marked the end of that labor peace at home.

ARCHIVAL: The wheels of the country's railroads grind slowly to a halt as 250,000 train men and engineers walk off the job.

NARRATION: This was a watershed moment for labor in the United States. Workers felt they deserved a share of those wartime profits, especially in a time of rising prices. Many UE workers voted to strike, alongside steel and auto workers - about a million and a half people in all. This was the closest thing to a “national strike” in U.S. history. These young, upstart CIO unions were flexing their muscles, and Big Business wasn’t liking it. Again, historian Bob Forrant.

Bob Forrant: 1946, 1947, there were massive strike waves in the country. There's steel strikes, coal strikes, railroad strikes, um, all these things are hampering the economy, and in 1946 congressional elections, Republicans essentially begin a campaign to blame a lot of the ills in America on unions, union organizing.

NARRATION: That fall, the Republican Party took control of Congress and brought in two new members: Richard Nixon and Joseph McCarthy. The newly-seated Congress quickly voted to limit labor unions’ right to organize and their ability to strike under the infamous Taft-Hartley Act.

Bob Forrant: Taft Hartley cripples labor from using some of its most effective tools. What Taft Hartley also does is it requires all union officers in the country to sign loyalty oaths, that says they not now nor ever were a member of the Communist Party.

NARRATION: Management did not have to take the oaths, just union leaders, who immediately smelled a rat. Here is the UE’s James Matles:

Matles Speech: In 1947, with the Taft Hartley Law, Bill was before Congress. And we told them this is a corporate setup, that they're doing a dirty job on the labor movement and on working people. And we had a slugfest there.

NARRATION: Labor leaders across the board initially refused to take the oaths, invoking their First Amendment rights of free speech; but within a year, 81,000 union officers representing 120 different unions gave in and signed affidavits. UE leaders on the other hand, from national officers to shop stewards, continued to refuse, arguing this was an unconstitutional ploy being used to divide and weaken the labor movement.

Bob Forrant: They're one of the few unions that on a principal basis refuses to go along with compelling people, to sign the loyalty oaths.

NARRATION: The loyalty oaths were meant as a deliberate shot across the bow to labor unions, particularly unions like the UE. This was the opening salvo in what was called the Red Scare.

ARCHIVAL (newsreel): Chairman J. Parnell Thomas of New Jersey opens an inquiry into possible communist penetration of the Hollywood film industry

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LfKSykTPzA4)

NARRATION: Today, the Red Scare is best known for Congressional hearings that featured Hollywood stars and liberals working in the State Department

ARCHIVAL: HUAC hearings

NARRATION: But it really got its start with labor unions. In 1947, months before those Hollywood hearings, a young Richard Nixon subpoenaed James Matles and fellow UE officer Julius Emspak, and subjected them to an aggressive round of questioning.

ARCHIVAL: Being called before these committees and harassed and threatened all because we had the guts to tell these committees to go to hell when they started their inquisition.

The UE attracted attention in part because it took strong positions on issues that impacted working people everywhere. It was the first union to support Black civil rights, and the first to make a stand for equal pay for equal work for women.

Bob Forrant: Organizing women workers, immigrant workers, Mexican workers, black workers. It's the radical edge of the labor movement that's really trying to do that work, not the mainstream.

NARRATION: But as cold war politics took hold of the nation, those positions the national UE took on domestic and foreign policy issues began to cause them problems. Here is retired UE organizer Dave Cohen again.

Dave Cohen: You know, the, the, the things that UE got in trouble for in the 1950s were mainstream CIO politics of the 1940s. You know, the CIO stood for a national health plan. It believed in social security. It believed in unemployment insurance, right? and the UE kept on to those radical ideas, but in the 50s, the political climate changed, right? And the union didn't change. Yeah, and the union didn't change, and some other unions caved in to that.

NARRATION: All this talk out of places like Washington and New York had little to nothing to do with what was happening in Greenfield. Coming out of the war, the UE was firmly established at Greenfield Tap and Die. Large negotiating teams made up of workers sat down with top brass from the company every year to hammer out contracts that included significant wage increases. Then a telegram arrived at GTD from a man named James Carey.

Carey was one of the original national union officers elected by UE members in the 1930s. He was dubbed the “Boy Wonder” because he was elected president of the UE at the age of 25. But by the late 1940s, the country had changed, and James Carey had too.

In 1948, Carey, who was no longer president of the UE, willingly traveled to Washington to testify that the union’s leaders were communists. This was a deep betrayal. Again, here is the UE’s Director of Organization, James Matles.

Matles Speech: During the McCarthy period, This union bled. How can any one of us who has gone through those days, those months and years, ever forget it?

NARRATION: That betrayal cut even deeper in the fall of 1949, when the UE was expelled from the CIO over its refusal to take the loyalty oaths or tone down its political statements. The UE was the first and largest of eleven unions to leave the CIO over this issue, accounting for over a million workers. It was now an unaffiliated, independent union.

Matles Speech: Oh, if this C. I. O. was not split, if that C. I. O. did not, was not wrecked by the corporations and their flunkies in Congress, and if the labor leadership did not cave in and crawl on its bellies, this country would be in a different shape today.

Bob Forrant: So the CIO expels, I think it's nine or ten unions,

NARRATION: Historian Bob Forrant.

Bob Forrant: and what they also do in a really, uh, incredibly cynical move that has long term impacts as well. They also start forming new unions to go to the factories that have the UE in place and persuade workers they don't want UE to represent them.

NARRATION: This new rival union was called the International United Electrical Workers, or IUE for short, and it was led by none other than James Carey. In November of 1949, Carey sent out 1,500 telegrams to management at UE shops across the country calling for immediate elections because, he said, the UE was now legally disqualified from representing workers. One of those telegrams went to Donald Millar, GTD’s banker president who spent weekends in Manhattan.

And Millar was quick to respond. At his direction, GTD stopped withholding union dues from paychecks until an election was held, bypassing the normal procedure for calling an election between rival unions. Greenfield was now the first testing ground in a national effort to take down the UE and replace it with what its rivals called a “real American union”.

Dave Cohen heard stories about this election, and the intense pressure that was brought to bear on Greenfield workers..

Dave Cohen: Priests picketing the factory every day threatening to excommunicate people. These government hearings denouncing the U. E. And then the newspapers urging the members there to vote out the UE.

NARRATION: Priests in eight Catholic churches across Franklin County instructed their parishioners to vote out the so-called “Christ-hating communists.” Protestant churches took out full-page ads in the Greenfield Recorder warning readers not to put their “faith in false gods.”The American Legion called on members to kick out the UE. The Saturday Evening Post, famous for its Norman Rockwell covers, wrote that UE members working in defense plants were a threat to national security. The Atomic Energy Commission then threatened to cancel government contracts with all UE shops.

Dave Cohen: just think about a charged atmosphere, people going to church and being told, if you vote for the UE you're going to burn in hell and your family's going to burn in hell. I mean, devout Catholics that be worrisome.

NARRATION: The rival union’s literature in Greenfield only spoke to the issue of international communism. They hosted a publicity stunt that offered $100 to charity if Hugh Harley, a highly popular organizer at GTD, took a loyalty oath with the Greenfield Town Clerk.

Leadership at Local 274 voted unanimously to stand by the UE. They said workers at GTD would be, quote, “insane” to jeopardize hard-fought gains in contract negotiations by switching to an unknown union.

Ballot boxes were set up by the National Labor Relations Board throughout both GTD plants. Members who wanted to vote for the UE had to mark their ballots with “No Union” since it was officially disqualified from running. The vote in December was so close, they scheduled a run-off election. Then, on January 24, 1950, GTD workers delivered their first shock. They voted, 396 to 332, to stand by the UE. The rival union’s first attempt to remove and replace the UE had failed.

But this success did not mark the end of the UE’s troubles. It was the beginning of what James Matles would later call, the Dirty Decade. That's coming up.

NARRATION: My name is Tom Goldscheider, I’m a public historian from western Massachusetts and this is “At Sword’s Point,” a radio documentary about a pivotal moment in American labor history. We’ve been following the story of the United Electrical Workers Union - or UE - which came under siege with the start of the Red Scare.

While reporting this project, my co-producer Ian Coss and I met with a local woman named Pam Murphy whose family story captures just how tense those years were in Greenfield…

Pam Murphy: This was um, this is always one of my favorite pictures. My sister wasn't born yet. I always say that.

Ian Coss: Could you say again what this is?

Ian Coss: Um, my dad, my brother, me, and my mom. Wow. On our front porch. What year is this, do you think? Um, probably 1950.

Ian Coss: So this is when he was working at GTD?

Pam Murphy: Um, yep.

NARRATION: Pam’s mother worked at Greenfield Tap and Die during the Second World War while her father was overseas. But when the men came back, her father took up a unionized job in one of the GTD plants.

Pam Murphy: He was a hard worker, handsome. I always thought he looked like Dean Martin. He had black curly hair. You know, he just he always taught all of us to if you believe in something, it doesn't matter what, if you believe in it, you go for it, and you get involved.

Tom Goldscheider: Do you think that was his attraction to, to, to the U. E.?

Pam Murphy: I do. Yeah. Yeah

NARRATION: Pam’s uncle also worked at GTD, but he was in management. The two families lived side by side in duplex apartments with a door between them. Pam was very small at the time, but she could tell that the union was a tense subject.

Pam Murphy: I think they kept it out of the house, but I'm sure being on different sides, there was friction there. And this is his brother in law, and it's like, what do you do, you're trying to stay nice, nice, and especially if you're all living together, Cause it was always open, you know, except at night, the hallway going across would be open.

Ian Coss: Yeah, can you imagine when the, when all the union drama was happening and the, the door between the houses is wide open?

Pam Murphy: Yeah, it would close then…

NARRATION: By 1950, when GTD workers voted to stand by the UE, the heat from the Red Scare was being felt all over Greenfield.

ACTOR READ: They put loudspeakers in every room in the factory and stopped production a couple of times every day telling us the union was full of communists and that we were a lot of Reds.

NARRATION: Workers at Threadwell, a small manufacturer of taps and dies on the other side of town, decided to organize with the UE. Here are the words of James Wooster, a machinist who worked there at the time:

ACTOR READ: We went around talking to the people and we told them, “don’t listen to that baloney.” I mean, what did we know about communism? We just wanted a union. We’d all been through the Second World War so we knew all about Hitler and Tokyo Rose trying to knock down your morale with their propaganda. This was just the same. You just had to look at who was saying it, to know it was a bunch of baloney.

NARRATION: The workers at Threadwell, many of them returned veterans, printed a public letter in the Greenfield Recorder in response to management’s use of Red Scare tactics:

ACTOR READ: We are loyal American workers and we are not tied up and will never be tied up with “sabotage” or enemies of the USA. So far as we are concerned, no one in the UE has ever been shown to be guilty of sabotage or acts against our country. The name calling and red smear against UE by yourselves and other unions does not impress us. We are grown men and we are the ones who will run our UE union – no one else.

NARRATION: Greenfield was bucking the trend. The UE was getting voted out of hundreds of plants across the country at this time, but workers in Franklin County were solidifying their support for the union. They voted the UE into Threadwell 54-36.

In 1952, with tensions in town still running high, Greenfield Tap and Die workers gathered under the marquee for “At Sword’s Point” for the vote that opened our program. This was actually a strike vote, and once again, the workers surprised everyone when they rejected advice from leadership at the union and voted not to strike. Even outspoken critics of the union were impressed by this demonstration of democracy. Workers got the last word at Local 274, which was now stronger than ever.

But then, the following summer, a member of the Local raised the alarm in this Letter to the Editor published in the Greenfield Recorder:

ACTOR READ: On August 17, 1953, We all came back from our vacations. Inside and outside the GTD plants there had not even been a whisper of any problems in our Union. Then, all of a sudden, an uproar broke loose in Greenfield. Red, communist, liar, cheat, sell-out Company union, affidavits, oaths, grand juries, jails and a thousand other wild words started flying around town like hailstones. In the newspapers, in ads, on the radio, in leaflets, we have been blasted from morning to night.

NARRATION: The rival union led by James Carey was taking yet another swipe at replacing the UE at Greenfield Tap and Die. This time, they followed federal guidelines and got a third of GTD workers to sign cards asking for an election. This is called a raid, when one union attempts to muscle into another union’s shop.

The difference this time around was that the heat was turned way up on the national UE by now. James Matles and fellow UE officer Julius Emspak refused to cooperate with Congressional hearings run by Richard Nixon and Joseph McCarthy. They faced charges of Contempt of Congress for their refusal to admit under oath that they were communists, and then name others in the union as communists. They risked serious jail time for not turning on their union brothers and sisters. And in the case of Matles – who was an immigrant – the threat of deportation.

Matles Speech: We knew that a few days before Christmas, the Justice Department will serve papers on us. The Un-American Committee will serve paper for us, on us. Injunctions will be issued against us. Always before Christmas. Make sure that everybody's sound asleep and they'll cut us down. Always before Christmas. Always before Christmas. And the labor leaders, and the corporations, and the company unionists, and Congress, and the administration, all hooked up to do the job.

NARRATION: Both Matles and Emspak ultimately fought their cases all the way to the Supreme Court, and won.

But it’s worth asking: What were these accusations of communism based on? Many of the founders of the UE were first or second generation European immigrants who brought their Labor Party politics with them. Likewise, many young union organizers took training courses run by the Communist Party in the 1930s.

Bob Forrant: These were places where people would learn labor history, organizing.

NARRATION: Labor historian Bob Forrant:

Bob Forrant: And you have to remember that there's no legal mechanism to figure out how one goes about forming a union. And it's really a, it's, it's literally and figuratively a fight.,and again, while not every person in the fight, um, is affiliated in some way with one of these training programs or one of these labor schools, certainly a lot of people are.

NARRATION: Even so, none of the investigations aimed at the UE turned up any evidence of disloyal behavior or foul play concerning the United States: no contacts with foreign agents and no tampering with military contracts.

In the end all the talk coming out of Washington did little to impress GTD workers who voted again to stay with the UE, this time by a solid 3-1 margin. This second vote would be the last challenge to the UE at Greenfield Tap and Die.

NARRATION: But there’s one last vote in our story. One last surprise.

Just weeks after fending off this second assault on UE Local 274, GTD workers voted overwhelmingly to go on strike – the first organized strike at the company.

Contract negotiations were stuck on wages and health insurance. The plan management was selling covered the cost of surgery, but the cost of anesthesia was out-of-pocket – no one was buying it.

One of the most impressive documents I came across in my research was a typed sheet of over a hundred names carefully arranged into three long columns. There were equal numbers of women and men divided into committees to support the strike. They set up soup kitchens in people’s homes near the picket lines, collected and distributed donations, wrote press releases and more. I saw here a unified effort that went beyond a handful of union officers.

This was a total, plant-wide shut-down. Machinists greased their tools before they walked off the job to make sure everything would be in working order when they returned. Picket lines were set up around the clock at both plants and the two sides settled after eleven days. Workers won the wage increases they asked for and got an improved health insurance plan that is still in effect in what remains of GTD today. As one worker put it: “It took the 1953 strike to teach GTD proper respect for the membership of UE Local 274.”

NARRATION: As the Red Scare intensified, the UE was voted out of major plants in Lynn, Springfield, Fitchburg and Pittsfield Massachusetts. National UE membership plummeted from a high of 600,000 in 1945, to fewer than 60,000 by 1960. But the propaganda that worked so well in other places backfired spectacularly in Franklin County. The louder the noise got, the more the workers pushed back.

Dave Cohen: it was sort of like people were Yankee Republicans. Especially Greenfield and up into Vermont. Um, and they didn't like anyone telling them what to do.

NARRATION: Dave Cohen remembers talking to Local 274 members about the Red Scare, and their UE organizer at the time, Hugh Harley.

Dave Cohen: And, you know, and I had people say to me, you know, Yeah, that Harley may have been a commie bastard, but, you know, he was our commie bastard. And no one's going to tell me whether he can stick around or not and they liked the union as democratic. They knew they ran their own locals with a fervor, you know, they ran their own locals and They didn't want anyone coming and telling them, you know, what the thing could do.

AMBI: Main St in Greenfield

NARRATION: Greenfield today stands in sharp contrast with the picture we get of Greenfield in the 1940s. A once-thriving Main Street is now dotted with empty storefronts. A plant that used to make silverware sets for the White House is now used as a treatment center for people struggling with opioid addiction. It’s fair to say that today, Greenfield is a shell of its former self.

Greenfield Tap and Die went through a series of mergers, starting in the late 1950s, that outsourced production of high-end precision tools. A venture capitalist eventually bought what was left of the company in the late 1980s, and closed the main plant. The much smaller Plant #2 still turns out taps and dies and its workers are still represented by UE Local 274.

Some people I’ve talked to say none of what you’ve heard here today makes any difference; that those jobs were destined to disappear just as they have all across America. In that case, why does it matter that GTD workers stood up for their union back in the 1950s? In truth, the UE was one of the only unions to seriously push back on plant closings. It created alternative models of production such as worker ownership. It was the last of the old-school, militant CIO unions from the 1930s that didn’t shy away from a fight.

The problem is that the UE, like Greenfield, is also a shell of its former self. It is still a vibrant union today, but it was cut down to just ten percent of its former size in the 1950s.

On first glance, it looks like an odd pairing: the perseverance of America’s most radical labor union in a deeply conservative, rural county. But after hearing their story, it makes sense. The workers at GTD never changed: they wanted respect and autonomy on the job and they valued the democratic process because that’s the way New England towns are traditionally run.

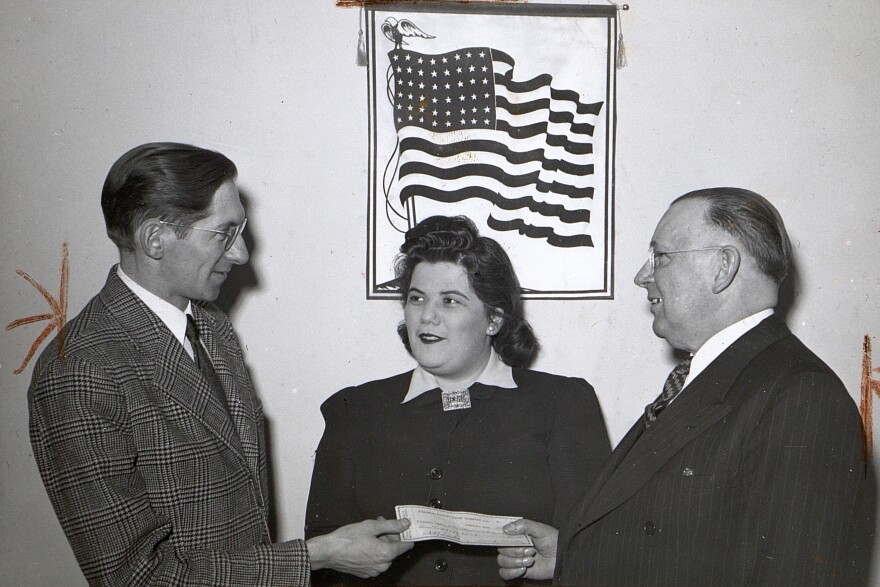

The day after GTD workers met for their strike vote at the movie theater where “At Sword’s Point” was showing, the Greenfield Recorder ran the story with a photo of them standing under the marquee in the early morning chill. The irony of the movie’s title, given all that UE Local 274 had just been through, was not lost on the person who wrote the caption.

A few pages in, the conservative newspaper, one of the oldest in the nation, published this editorial that also speaks to where we find ourselves today. It read: “A sense of mutual responsibility between employer and employee… cannot continue if any class is deprived of fair treatment. Unless a proper balance is maintained, our only path is downward.”

At Sword’s Point is produced by Ian Coss and me, Tom Goldscheider. Karen Brown provided editorial guidance, and John Voci provided production assistance. The archival text was read by Jim Frangione. Our program was supported by Mass Humanities, New England Public Media, the Museum of Our Industrial Heritage in Greenfield, and the Greenfield, Montague Cultural Councils and the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

A collection of quotes that sheds additional light onto the story we tell in “At Sword’s Point.”

Quotes compiled by Tom Goldscheider.

“When industrious mechanics form a co-operative association for the purpose of placing the fruits of their skill and labor in the market without the aid of capitalist and employer, they do more for the cause of working men than all the ‘Unions’ and ‘strikes’ in the world, and will receive the hearty support of the public.”

(The inventor of taps and dies started a worker-owned cooperative with other Greenfield machinists that was subsequently bought out by local investors.—Greenfield Gazette, April 1871)

“It is entirely safe to say that the average wage paid [in Greenfield] is nearly twice that paid to factory employees in the state, where the average earnings of factory employees are higher than in any other state in the country, and this country leads the wage standard of the world." (Western New England magazine, July 1912)

“There were other good men in the factory doing great work. One was Randolph Suhl who would grind small gages to .0003 tolerance and continue to do it all day. That takes skill, knowledge of the machine and patience.” (Greenfield Tap and Die produced a third of the world’s gages, tools that are essential to the use of interchangeable parts.)

“Mr. Clancy greatly improved the old style of threading machine, rebuilding it so that it would do seven or eight times as much work as formerly, and then re-designing it again so that the output was again multiplied by seven or eight.” (Machinists like John Clancy, who left school at age eleven, were called the “backbone” of the tap and die industry.—The Helix magazine,January 1921)

“That employees shall have the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and shall be free from the interference, restraint or coercion of employers of labor or their agents” (7A National Industrial Recovery Act [1933], the law that helped open the floodgates to union organizing in the 1930s.)

“We will decide what we will ask in our UE contract with Threadwell. But we have no intention of insisting on demands which would make the company lose money and close. After all, we make our bread and butter in Threadwell. Frankly, we think the company is stretching things a bit on this, in order to scare us. We are not scared.” (Taken from an open letter to management at Threadwell, a smaller maker of taps and dies in Greenfield, signed by 65 workers. (Greenfield Recorder, April 12, 1951)

“If you want to maintain democracy in our organization, if you want officers and representatives to whom no shop grievance is too small to handle, no matter whether it affects one worker or one penny, you must have an organization where your officers and your organizers feel like the members and not for the members. There is a big difference.” (UE Director of Organization James Matles from his memoir, Them and Us. UE officers’ salaries could not exceed that of the highest paid member represented by the union.)

“There is a difference between political action and playing politics. When we fought the politicians and we won the legislation we did, we didn’t play politics; we engaged in political action. We didn’t rub bellies with politicians. There was plenty of air between us.”

(James Matles from his memoir, Them and Us.)

“The overwhelming number of the 531 members are businessmen or lawyers whose main private occupation has been defending the property rights of corporations and the wealthy. Labor and colored people are sadly unrepresented in Congress… There are several times as many outright millionaires in Congress as there are trade unionists.” (Bold statements like this set the UE apart from other labor unions in the 1950s. UE General Officer’s Report presented at its 1957 Annual Convention.)

“The problems of the U.S. can be summed up in two words: Russia abroad and labor at home.” (G.E. Chairman Charles Wilson offering his view of the political landscape in 1946.)

“Let us all be careful that we do not play the bosses’ game by falling for the Red Scare. No union man worthy of that name will play the bosses’ game.” (Walter Reuther, a rising star at UAW, responding to the loyalty oaths mandated in the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947. Less than a year later, he took the oath and then called out leaders at the UE for not following suit.)

“Left-wing unions will cause the destruction of democratic trade unions.” (CIO President Philip Murray justifying the expulsion of the UE from the CIO. Ironically, the UE was much more democratically run than the unions that replaced it.)

“As soon as you band together in a union you are termed a radical, a trouble-maker, a red or a Communist.” (UE President Albert Fitzgerald speaking to GTD workers in Greenfield in the run-up to the election that pitted the UE against the rival union.)

“As a citizen of the United States of America, I despise the philosophy of the Communist Party. But as a member and officer of the union, I will not let that issue tear this union apart.”

(UE President Albert Fitzgerald, who began his career working as a machinist at Lynn G.E.)

“You’ve got nothing on me, not a damned thing. You’ve been trying to frame me on my non-communist affidavits for three years, the pair of you, and you haven’t done it. Let me ask you a question: Are you a spy? That question is as good coming from me to you as coming from you to me.” (James Matles, under oath, confronting his accusers: Senator Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn.)

“Rulers have always ‘redbaited’ anyone who stirred up the people. They have tried to identify him with some bogy word like sedition, treason, subversion, conspiracy, revolution, anarchism, socialism, and above all, communism. The technique was to popularize the word as one of horror or fear to the unthinking; then link your opponent with it – how accurately mattered not – in a way to include him in the emotional prejudice the word was intended to stir.” (Len De Caux in his memoir Labor Radical,1970)

“This is a lot of bull – and that’s all I can say about it.”

(Greenfield’s UE Local 274 President Daniel Nadeau in response to a proposed mandate that all UE organizers in Massachusetts take additional loyalty oaths. —Recorder, October 11, 1955)

“The first thing I told them was that the RED business would never work at GTD or anywhere else in Greenfield.” (Letter to the Editor —Recorder, October 28, 1953)

“UE local stewards used neither threats or pressure… the UE members don’t bother the people who are working for the IUE.”

(UE Local 274’s Chief Steward at Greenfield Tap and Die. There were no arrests connected to union elections that pitted the UE against the rival union. —Recorder, September 30, 1953)

“So long as the democratic spirit survives in the United States, there will be dissenters from any majority action. They have the right to be heard, so long as their arguments conform with the laws of the land and of society.” (Taken from an editorial published by the Greenfield Recorder on April 10, 1952, the same day workers were photographed under the marquee for “At Sword’s Point.")

At Swords Point: The United Electrical Workers Union and the Greendfield Tap & Die Company, Tom Goldscheider from The Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Winter 2019